PROTON: A Relational Foundation Model for Neurological Discovery

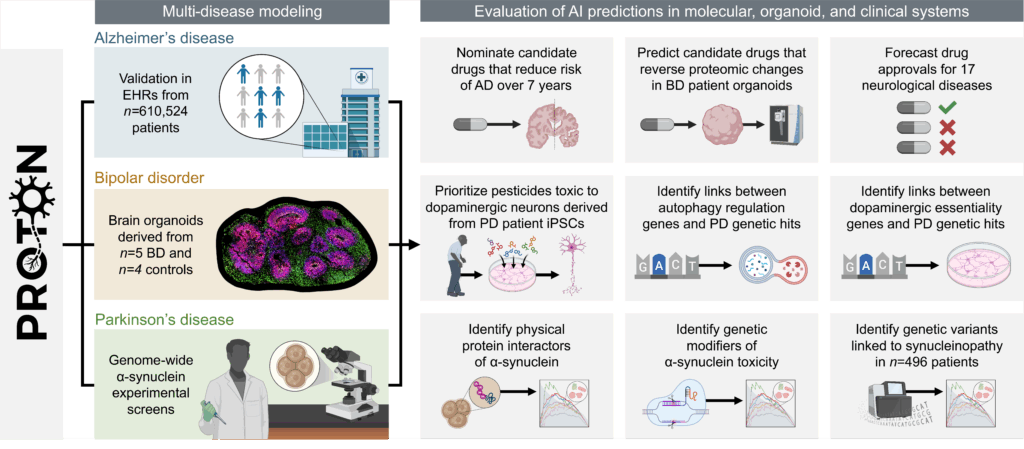

January 26, 2026Foundation models have transformed AI by scaling sequence-based learning, but many scientific problems are not naturally sequential. In neuroscience, insight depends on relationships across genes, cell types, and brain systems. This work introduces a relational foundation model for neurological discovery and evaluates it through discovery loops that connect AI predictions to experiments in Parkinson’s disease, bipolar disorder, and Alzheimer’s disease.

Neurological discovery depends on making sense of biology across scales, from molecular interactions to cell-type programs to brain-wide organization. The stakes are high: neurological diseases are the leading global cause of disability and the second leading cause of death. Every year, these conditions contribute to over 11 million deaths and account for roughly one in three years lived with disability, affecting more than 3 billion people worldwide. Despite this burden, for most neurological diseases there are still no treatments that can slow disease progression.

Foundation models offer a powerful new set of tools for navigating this complexity. But progress is constrained by model capacity and how we evaluate scientific insights generated by these models. Too often, these models are judged by their performance on fast-saturating benchmarks or their ability to recover retrospective labels. These shallow evaluations reward pattern matching but do not test whether predictions give new biological insights.

In neurology, the distance from a molecular hypothesis to patient benefit is already long: a candidate mechanism must survive years of work, from perturbation experiments to clinical studies, and most ideas fail along the way. The bottleneck is not only generating predictions, but carrying them across this chain of evidence. Existing foundational models are optimized for in silico performance instead of real-world scientific discovery.

We developed PROTON, a relational foundation model for neurology. PROTON is a relational reasoner trained on a multimodal knowledge graph contextualized to the adult brain that links genes to gene programs across cell types and spatial maps of brain regions. We paired PROTON with wet lab campaigns to evaluate it against genome-wide screens, patient-derived brain organoids, and patient personal health data in neurology (Figure 1).

Our Approach: A Relational Foundation Model

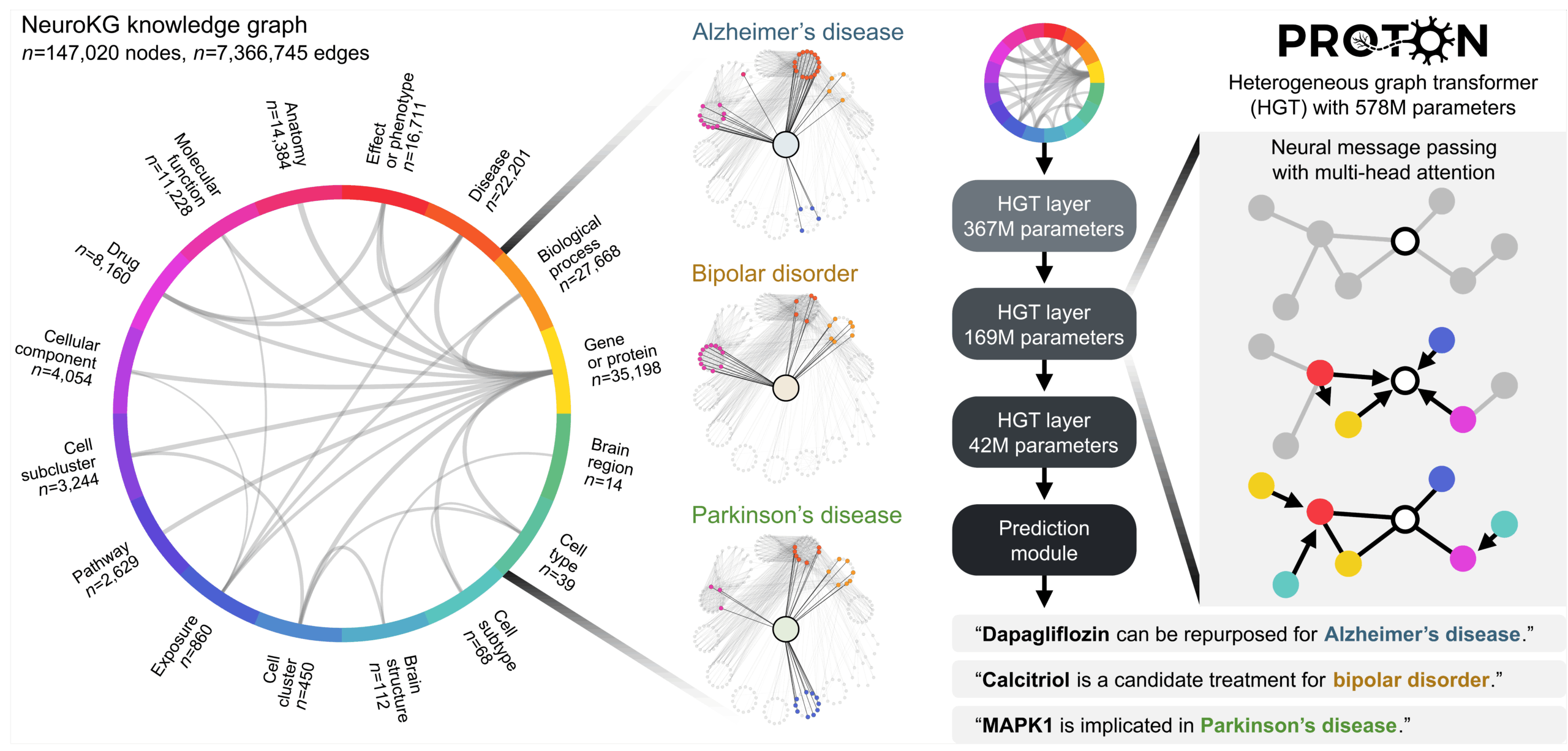

Our approach reframes what a foundation model reasons over. Instead of treating the world as a sequence of tokens, PROTON treats it as a system of relationships (Figure 2). Sequence models learn by predicting what comes next in a linear order. Relational transformers learn by integrating information across connected entities, where meaning arises from structure and the links between entities rather than from position in a sequence.

This changes the modeling problem. Instead of asking the model to map (input token sequence) → (next token in the sequence), we ask it to map (seed node + graph context) → (hypothesis linked to the graph context). Through neural message passing with attention, PROTON propagates information across millions of graph contexts, learns which neighbors and relation types are most informative, and uses multi-hop graph context to generate predictions.

For example, for Parkinson’s disease, our prompts can be: (Parkinson’s disease node + Genetic association graph context) → (Candidate genes), followed by another prompt (Candidate gene + α-synuclein protein-protein interaction graph context) → (Candidate interactors), and finally identifying which of these relational paths connect to dopaminergic neuron survival pathways. We will return to this concrete prompt in the Parkinson’s section.

Relational Discovery in Parkinson’s Disease

We first evaluated PROTON in Parkinson’s disease using the relational prompt introduced above: (Parkinson’s disease node + Genetic association graph context) → (Candidate genes), followed by (Candidate gene + α-synuclein protein–protein interaction graph context) → (Candidate interactors), and then asking which relational paths connect to dopaminergic neuron survival pathways. Using this formulation, PROTON’s predictions were confirmed as hits by six genome-wide α-synuclein screens, with strong enrichment across experimental modalities (MYTH NES = 2.30, APEX2 NES = 2.16, TES NES = 2.13; all FDR < 1×10⁻⁴) (Figure 3).

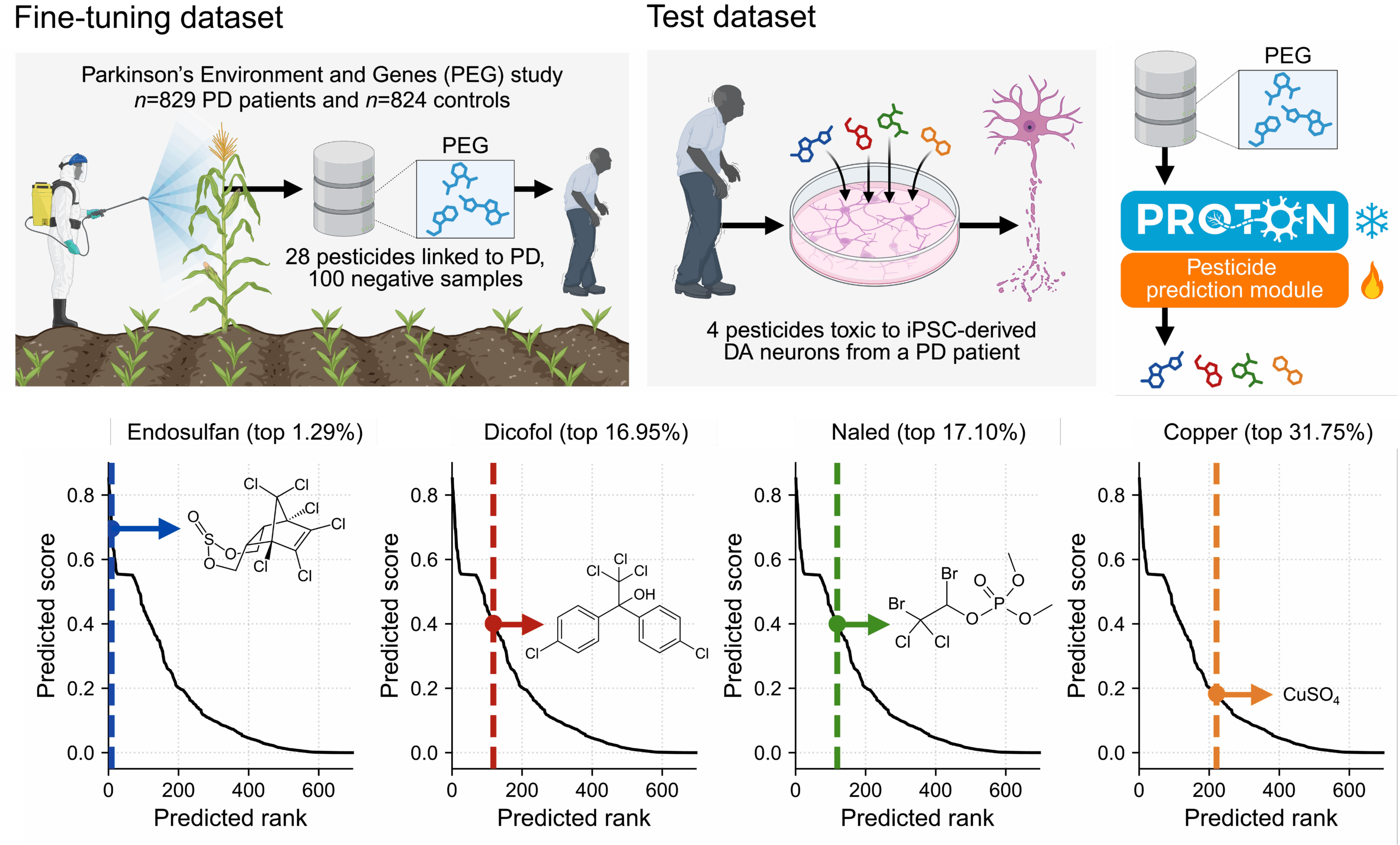

We then applied the same relational reasoning approach to ask how environmental pesticide exposure influences dopaminergic neuron health and alters Parkinson’s disease risk. After a few-shot adaptation using a dataset of 28 pesticides from epidemiological analyses of agricultural exposure and PD incidence, PROTON evaluated pesticide graph context and predicted candidate neurotoxicants, including endosulfan, ranked within the top 1.29% of all chemicals (Figure 4). We tested these predictions in patient-derived dopaminergic neurons, linking population-level exposure signals to cell-type-specific molecular toxicity.

Finally, PROTON linked genetic risk to dopaminergic neuron survival (Figure 5) using a relational prompt: (Dopaminergic neuron survival node + CRISPR essentiality graph context) → (Candidate survival genes), followed by another prompt: (Candidate survival gene + genetic association graph context) → (Parkinson’s disease links). Anchoring the model on 288 PD-associated genes, we asked whether these relational neighborhoods converged on results from a whole-genome CRISPR essentiality screen of 681 genes required for dopaminergic neuron survival. PROTON preferentially connected dopaminergic-essential genes to PD genetic hits compared with GWAS hits from ten other diseases and highlighted relational paths linking common-variant loci to a rare-variant autophagy module that include EXOC4 and HAX1. These results show how PROTON uses graph context to connect genetic associations to mechanisms of neuronal degeneration.

PROTON Predicts a Drug that Restores Bipolar Organoid Proteomes

We next moved from molecular and genetic hypotheses to drug prediction. We used PROTON to predict candidate drugs for bipolar disorder, a chronic neuropsychiatric condition. A key challenge is evaluation: no animal model or single experimental system captures the clinical syndrome seen across patients. Patient-derived brain organoids provide a complementary in vitro experimental system that preserves disease genetic backgrounds and cell-type programs, enabling direct tests of whether a model-predicted drug produces measurable effects.

We paired PROTON with a patient-derived cortical organoid model of BD (Video). Using a relational drug prompt, starting from the BD node and leveraging drug-target, pathway, and cell-type graph context, PROTON predicted calcitriol as a candidate drug. In collaboration with the Wyss Institute, we treated cortical organoids from n = 5 BD patients and n = 4 healthy controls with calcitriol for one week and performed unbiased deep proteomic profiling.

Four of five treated BD organoids shifted toward the control proteomic state relative to untreated BD organoids (Figure 6), indicating normalization of disease proteomic programs. Calcitriol treatment also reversed ADAR overexpression in this organoid model, consistent with effects on RNA editing pathways implicated in BD. In proteomics, calcitriol showed effects that are distinct from, and partially overlapping with, lithium, the frontline BD therapy with high long-term relapse. These results provide a molecular evaluation of a PROTON-predicted candidate drug in a patient-derived neuroscience model.

PROTON Predicts Drugs Linked to Lower Seven-Year Risk for Alzheimer’s

Finally, we evaluated whether PROTON’s drug predictions carry signals in large-scale longitudinal patient data for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Using a relational drug prompt, starting from the Alzheimer’s disease node and leveraging graph context of drug-targets and disease phenotypes, PROTON predicted candidate drugs for evaluation. We then evaluated eight predicted candidates using longitudinal electronic health record data from 610,524 patients in the Mass General Brigham healthcare system. In retrospective survival analyses, five of the eight candidates are associated with reduced seven-year dementia risk (minimum hazard ratio = 0.63, 95% CI = 0.53–0.75, p = 1×10⁻⁷) (Figure 7). These population-scale associations provide an independent validation signal for model predictions and help prioritize which hypotheses merit deeper mechanistic study.

Conclusion

Neurological disease is shaped by relationships across genes, proteins, cell types, and brain systems. PROTON is built around this idea. It is a relational foundation model that reasons over graph context, rather than treating biology as a set of disconnected prediction tasks.

We used PROTON to generate hypotheses in Parkinson’s disease, bipolar disorder, and Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. We evaluated these hypotheses using genome-scale molecular screens, patient-derived brain organoids, and longitudinal electronic health record data. To our knowledge, no prior study has paired a foundation model with experimental and population-scale evaluation at this breadth and scale.

This study illustrates how scientific discovery can proceed through loops between AI and real-world experiments. AI models generate hypotheses, experiments test and refine them, and human scientists guide the next round of questions. PROTON operates within this loop to support iterative scientific discovery, not solely one-shot prediction.

PROTON is an open-science, open-weight model. The code, training datasets, and model weights are available at the links below.