Into the Rabbit Hull-Part II

November 24, 2025

This blog post, the second part in a two-part series, examines DINOv2’s geometry and proposes the Minkowski Representation Hypothesis as a refined view of the current phenomenology.

In this second part of a two-part blog post, the authors ask the fundamental question: is the linear view of DINOv2 under the Linear Representation Hypothesis (LRH) sufficient to describe how deep vision models organize information? The authors examine the geometry and statistics of the learned concepts themselves and the results suggest that representations are organized beyond linear sparsity alone.

This blogpost is the second part of our series Into the Rabbit Hull: From Task-Relevant Concepts in DINO to Minkowski Geometry. Having previously analyzed DINOv2 under the Linear Representation Hypothesis (LRH) — where activations are treated as sparse linear combinations of quasi-orthogonal features — we now turn to a more fundamental question: is this linear view sufficient to describe how deep vision models organize information? In this second part, we examine the geometry and statistics of the learned concepts themselves. Together, our results suggest that representations are organized beyond linear sparsity alone.

Synthesizing our observations, we explore a refined view: token as sum of convex mixture. This view is grounded in Cognitive theory of Gärdenfors’ conceptual spaces as well as in the model’s own mechanism: each attention head produces convex combinations of value vectors, and their outputs add across heads; tokens can thus be understood as convex mixtures of a few archetypal landmarks (e.g., a rabbit among animals, brown among colors, fluffy among textures). This points to activations being organized as Minkowski sums of convex polytopes, with concepts arising as convex regions rather than linear directions. We finish by examining empirical signals of this geometry and its consequences for interpretability.

Explore the interactive demo

DinoVision

Statistical and Geometrical Analysis of the SAE Solutions

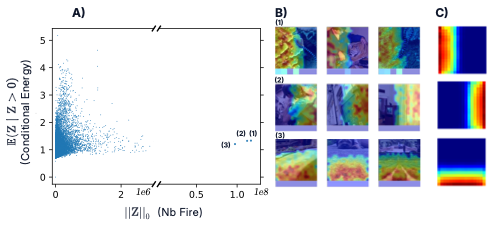

In the first part, we examined which concepts were recruited by each task. We now turn to the concepts themselves: do they all activate with similar frequency? With the same intensity? To answer this, we study the activation statistics of the SAE codes \(Z\). A useful diagnostic is the conditional energy — the average activation magnitude of a concept given that it fires. Plotting conditional energy against activation frequency reveals a triangular envelope: rarely active concepts tend to fire more strongly when they do activate, whereas frequent ones remain weaker on average. In other words, certain features dominate the representation norm-wise, while others contribute marginally. This may reflect a phenomenon of feature-norm dominance, where a few high-energy features occupy disproportionate norm in the activation.

Among all concepts, three appear as outliers: they fire almost continuously across the entire dataset. Visual inspection shows that these concepts encode positional information — indicating whether a token lies on the left, right, or bottom of the image grid. This observation adds nuance to the assumption that the representation is strictly sparse. Instead, DINOv2 exhibits a hybrid regime, where a small set of universally active, spatially grounded features coexists with a large ensemble of highly selective, image-dependent ones — combining aspects of both sparse and dense low-rank representations.

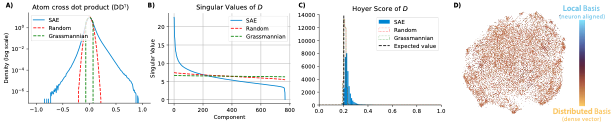

Having characterized the statistics of activations, we now turn to the geometry of the dictionary D: the set of directions used by the SAE to reconstruct activations. Its structure informs us about how representational capacity is distributed — whether uniformly across all directions (as in an ideal Grassmannian frame), or anisotropically along preferred directions. Relative to isotropic random vectors (as at initialization), the learned dictionary does not approach the uniform incoherence of a Grassmannian frame. Instead, it evolves in the opposite direction, showing higher coherence and clustering. This departure from the optimal feature-packing regime suggests that DINOv2 favors structured redundancy, perhaps supporting specialization or compositional reuse of features.

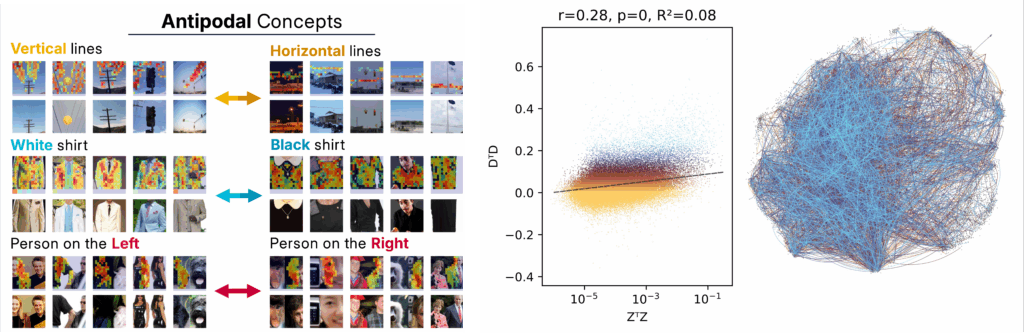

A notable pattern emerges in the tails of the dot-product distribution: a small but consistent set of antipodal pairs ($D_i \approx -D_j$). These correspond to semantically opposed features — such as “left vs. right” or “white vs. black” — encoded along shared axes but with opposite polarity. Practically, this antipodal structure complicates the use of cosine similarity for retrieval or clustering, as negative correlations may indicate contrastive variants rather than unrelated concepts. Finally, the singular-value spectrum of $D$ reveals that, despite being overcomplete, the dictionary spans a low-dimensional subspace. This anisotropic allocation of capacity suggests that some directions are densely populated and overrepresented, while others are sparsely or not used at all — another deviation from the idealized sparse-coding view.

Lastly, we examine the interaction between statistics and geometry: are concepts that often co-activate also close in the geometric sense? To test this, we compare the co-activation matrix $Z^\top Z$ — capturing how frequently pairs of concepts fire together — with the geometric affinity matrix $D D^\top$. We find only a weak but statistically significant correlation between the two. Concepts that frequently co-occur are not necessarily neighbors in feature space, and geometric proximity does not reliably predict joint activation.

Together, these findings highlight the limits of the purely linear, sparse-coding framework. DINOv2’s representation includes dense positional features alongside sparse ones, coherent clusters and antipodal pairs instead of near-orthogonal atoms, and low-dimensional task-specific subspaces. Such properties are difficult to reconcile with a simple superposition model and instead point to additional geometric constraints shaping the representation. To probe this structure more directly, we next turn to the local geometry of image embeddings.

The Shape of an Image

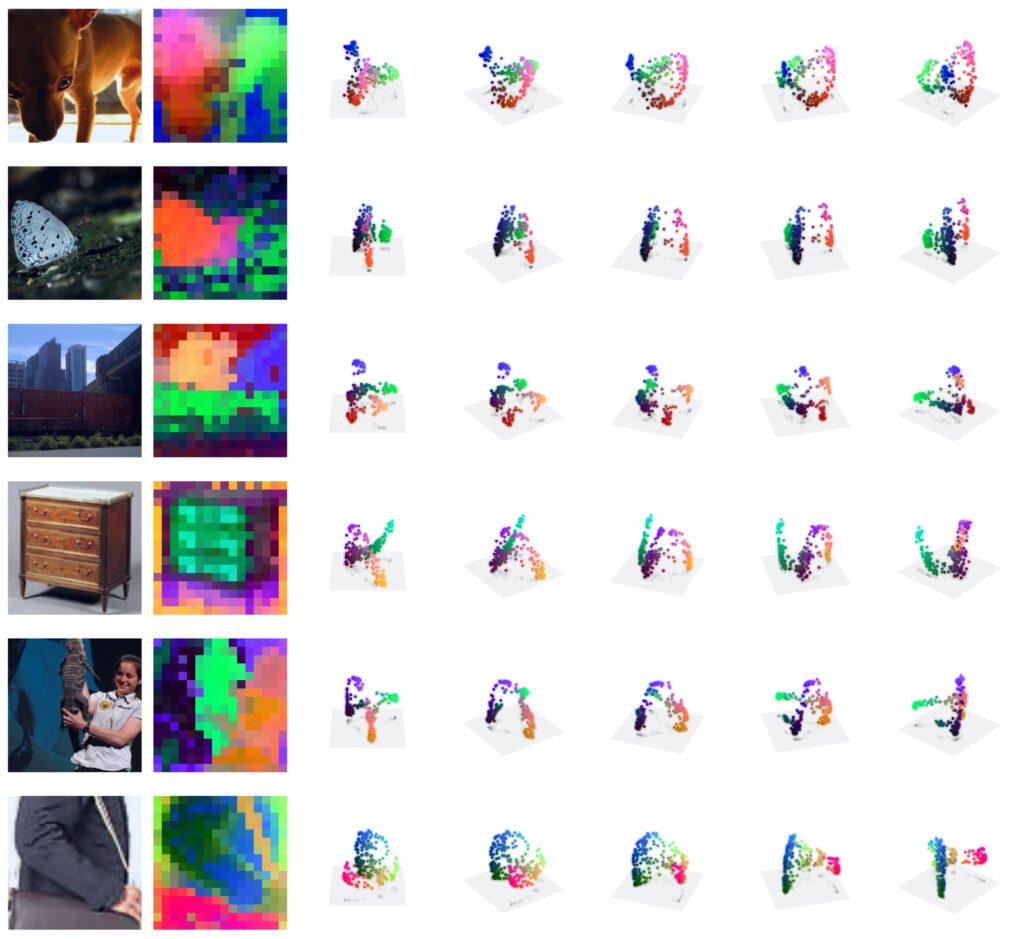

Our goals in this section are twofold: (i) turn to the model-native geometry and demystify what PCA actually captures in single-image embeddings, particularly the origin of the observed “smooth” structure; and (ii) to characterize token-level geometry across layers without presupposing a sparse, near-orthogonal coding model.

Just position? A natural hypothesis is that this local connectedness simply reflects positional encodings. To test this, we quantified positional information across layers by training linear decoders to recover each token’s spatial coordinates. Early layers indeed preserve high-rank positional embeddings, allowing near-perfect decoding of (i,j) locations. However, as we move deeper, the positional subspace collapses to two dimensions, roughly corresponding to horizontal and vertical axes. This compression resembles a shift from place-cell to axis-based coding — precise localization giving way to continuous spatial axes. Interestingly, this compression cannot fully explain the observed connectedness. When projecting real image embeddings, components corresponding to position appear only around the third to fifth principal components, not the dominant ones. Furthermore, when we explicitly remove the positional subspace, the PCA maps remain locally connected. Thus, the observed structure is not an artifact of positional encoding but a genuine property of the learned representation.

Across many images, we found that tokens consistently lie on low-dimensional, locally connected manifolds that align with objects and coherent regions. Their stability across inputs suggests that embeddings are not purely relative: DINOv2 has learned a geometry anchored to shared semantic coordinates. The persistence of smooth structure even after removing position can suggest an interpolative geometry — tokens behaving as mixtures between a small number of latent landmarks.

This interpretation aligns with the model’s training objectives. Both the global DINO head and the iBOT head operate over large prototype vocabularies (128k each), while the entropy-maximizing regularization encourages tokens to distribute uniformly among these prototypes. Consequently, each token becomes a convex mixture of archetypal points drawn from these prototype systems. The apparent “smoothness” of PCA maps thus reflects mixture geometry — not continuous interpolation, but structured combination of discrete archetypes.

In the next section, we formalize this intuition and show that transformer attention itself — by producing convex combinations of value vectors across heads — naturally gives rise to this landmark-based, Minkowski geometry.

The Minkowski Representation Hypothesis

While hypotheses about representational composition are rarely stated explicitly, the geometry assumed by our methods is important: it constrains both their validity and the phenomena they can reveal. If sparse autoencoders implicitly answer to the Linear Representation Hypothesis, then we understand the importance of specifying the correct ambient geometry: it not only conditions how we interpret representations, but also determines the very form that our analytical methods of concept extraction can take.

Armed with our preceding observations, we contend that an alternative account can explain the phenomena we documented, in particular the interpolative geometry within single images. The Minkowski Representation Hypothesis (MRH) proposes such a geometry. In this view, activations form as Minkowski sums of convex polytopes, each corresponding to a group of archetypes or “tiles.” A token’s embedding thus results from a few active tiles, each contributing a convex combination of its archetypal points — for instance, an “animal” polytope capturing categorical features, a “spatial” one encoding position, and a “depth” one encoding scene geometry. Tokens are therefore convex mixtures of archetypal landmarks, not linear combinations of independent features.

This organization naturally emerges from the architecture itself. Each attention head computes convex combinations of its value vectors (via softmax weights acting as barycentric coordinates). These convex outputs are then added across heads — an operation that corresponds precisely to a Minkowski sum. The resulting representational space is thus formed by the additive composition of convex hulls across attention heads, a structure the MRH formalizes mathematically.

Preliminary empirical evidence supports this geometry. First, when interpolating between token embeddings, linear paths rapidly drift away from the data manifold, while piecewise-linear paths that follow k-nearest-neighbor graphs remain close to valid activations — consistent with movement along polytope faces rather than through empty space. Second, Archetypal Analysis, a convex-constrained model equivalent to the single-tile case of MRH, reconstructs activations nearly as well as an SAE while using only a handful of archetypes per image. This implies that tokens lie near low-dimensional convex hulls within the embedding space. Third, archetypal coefficients show block-structured co-activation, revealing that archetypes naturally cluster into groups — the very “tiles” predicted by the MRH. These observations together point to a representational structure governed by convex composition rather than linear superposition.

Implications for Interpretability

If the MRH holds, three consequences follow for how we study and manipulate concepts.

1. Concepts as Regions.

Under MRH, a concept is not a direction but a region — a convex cell or landmark within the manifold. Semantic membership depends on proximity to archetypal points rather than projection along a vector.

2. Bounded Steering.

In a convex geometry, steering an activation along a concept saturates once it reaches the boundary of the corresponding region. This explains why feature probing and scaling often show plateauing or reversal: the embedding leaves the valid convex cell once it passes the archetype’s basin of attraction. Effective probing thus requires measuring how close an activation moves toward a landmark, rather than extrapolating along an unbounded direction.

3. Fundamental Non-Identifiability.

Unlike linear decompositions, Minkowski sums are non-unique: different combinations of convex polytopes can produce the same resulting space. In other words, from the final activations alone, it is impossible to uniquely recover the underlying constituent regions. This mathematical impossibility places limits on post-hoc interpretability.

However, this impossibility, at its core, also hint a possible direction. While the final Minkowski sum hide its constituent factors, the information to find the decomposition is available within previous intermediate representations. Accessing attention weights and activations from earlier layers may render the factorization tractable, and pointing interpretability efforts toward exploiting architectural structure rather than treating learned representations as opaque geometric objects. We believe that developing these structure-aware interpretability techniques could yield promising advances in

concept extraction.

Summary

In this second part, we investigated the geometry and statistics of DINOv2’s learned concepts. Our analysis revealed several empirical patterns — anisotropy aligned with task subspaces, dense positional features, antipodal semantic axes, and locally connected manifolds in token embeddings. These findings indicate that the representational space may organize itself in ways not fully captured by simple linear sparse coding.

Building on these observations, we proposed a a refined view, grounded in the model mechanism and inspired by Gärdenfors cognitive theory of conceptual space: the Minkowski Representation Hypothesis (MRH). In this framework, activations are understood as convex mixtures of archetypal landmarks, and transformer attention naturally implements this geometry by combining convex hulls of value vectors across heads — forming what can be seen as Minkowski sums of polytopes. Preliminary analyses are compatible with this view.

If such a geometry indeed plays a role, it carries implications for how we interpret learned concepts. Concepts may behave more like regions than directions, steering effects may saturate once embeddings reach the boundary of valid convex regions, and interpretability from activations alone may face limits due to the non-uniqueness of Minkowski decompositions.

That said, these findings should be viewed as exploratory. They do not invalidate the linear picture but rather suggest that the Linear Representation Hypothesis may be a first-order approximation of a richer geometry. We show that understanding this geometry more precisely will require structure-aware approaches. In this sense, the Minkowski view is less a replacement than a refinement and extension of the linear perspective — a hypothesis pointing toward the geometric subtleties that deep vision models may implicitly develop.