Forecasting the Brain: Scalable Neural Prediction with POCO

February 06, 2026Predicting future neural activity is a critical step toward achieving real-time, closed-loop neurotechnologies. To this end, we introduce POCO, a unified forecasting model trained on diverse calcium imaging datasets across species—from zebrafish to mice. POCO achieves state-of-the-art accuracy by combining lightweight individual predictors with a global population encoder, and it demonstrates the ability to rapidly adapt to new individuals and uncover meaningful embedding without supervision.

The Premise: Forecasting for Closed-loop Neurotechnology

The ultimate goal of computational neuroscience is not just to analyze the brain, but to interact with it. To build effective closed-loop technologies—systems capable of suppressing seizures, guiding prosthetics, or modulating brain states in real-time—we need models that can do more than fit historical data. We need models that can accurately predict the brain’s future state.

While recent advances in large-scale neural recordings have given us access to dynamics across populations of neurons, most existing models focus on interpreting latent features or decoding behavior. Forward prediction—in which we estimate the cascade of activity from a catalyzing event, several seconds in the future—remains underexplored, particularly for calcium imaging data recorded during spontaneous behavior. Furthermore, current approaches are often “single-session” models: they are trained from scratch for each animal, failing to leverage the shared neural motifs that exist across individuals and limiting flexible use.

Our research question was driven by this gap: Can we build a scalable, multi-session model capable of forecasting brain-wide activity? Such a model would serve as a “foundation model” for neural dynamics—pre-trained on vast amounts of data and capable of generalizing to new subjects for real-time applications.

The Approach: Population Conditioning

Forecasting neural activity presents a trade-off. Simple univariate models (predicting a neuron’s state based solely on its own history) are efficient, but they miss the broader context. Complex multivariate models capture interactions, but often struggle to scale to the tens of thousands of neurons found in whole-brain recordings.

To solve this, we developed POCO (POpulation-COnditioned forecaster).

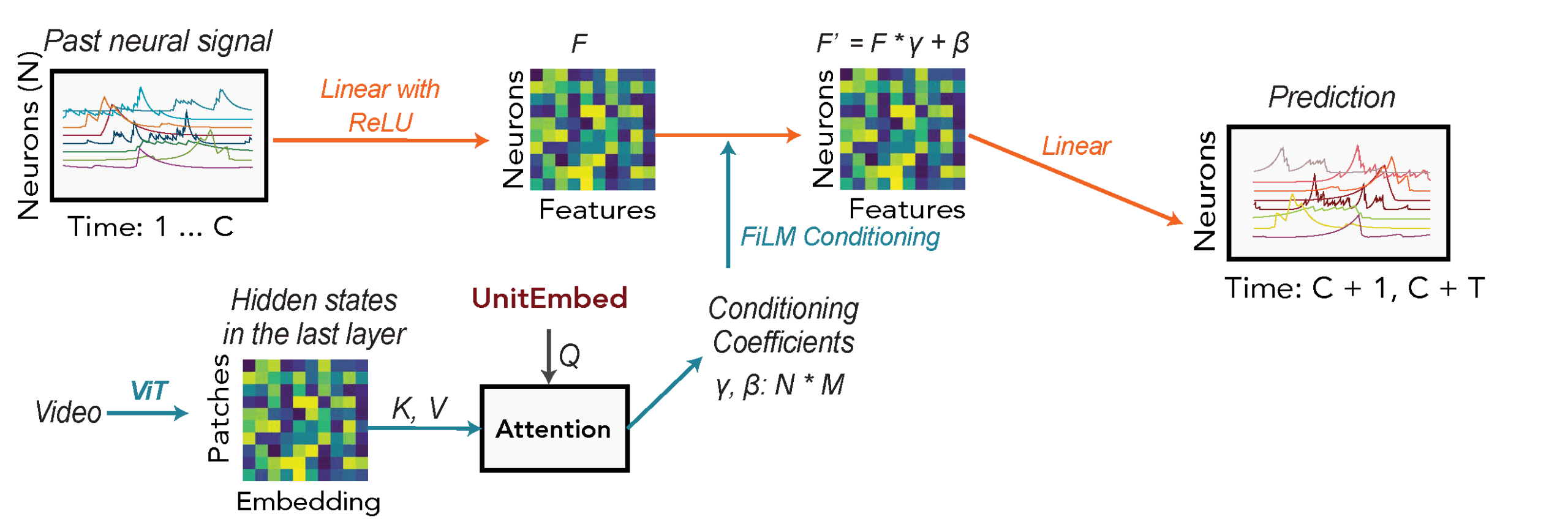

POCO comprises two synergistic components:

- A Univariate Forecaster: We use a simple Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) to model the temporal history of each individual neuron. This component acts as a local specialist: it focuses solely on a neuron’s own past to capture its specific auto-correlative properties and temporal patterns.

- A Population Encoder: Simultaneously, this separate attention-based network acts as a synthesizer, processing the activity of the entire population to generate a compressed summary of the global brain state. To bypass the prohibitive computational costs of handling tens of thousands of neurons with standard Transformers, we adapted the POYO architecture (based on Perceiver-IO).

- First, we “tokenize” the neural activity by chopping the continuous traces of each neuron into short temporal segments.

- Crucially, rather than attending to every token, the model uses a small, fixed set of learnable latent vectors to “query” the population data. This creates an information bottleneck that forces the model to compress the massive, high-dimensional input into a compact, fixed-size summary. This design allows the encoder’s compute cost to scale linearly—rather than quadratically—with the number of neurons, making whole-brain processing feasible.

The innovation of this approach lies in how these two systems meet. We use a mechanism called Feature-wise Linear Modulation (FiLM) to let the global population state “condition” the local forecaster. The Population Encoder outputs specific “conditioning parameters” (scale and shift factors) that directly modulate the internal activations of the Univariate Forecaster. In effect, the global brain state dynamically “tunes” the local predictor at every time step. This allows the simple MLP to adjust its forecasting rules based on the broader context—what the rest of the brain is doing—efficiently capturing both local temporal statistics and global system dynamics.

State-of-the-Art Accuracy

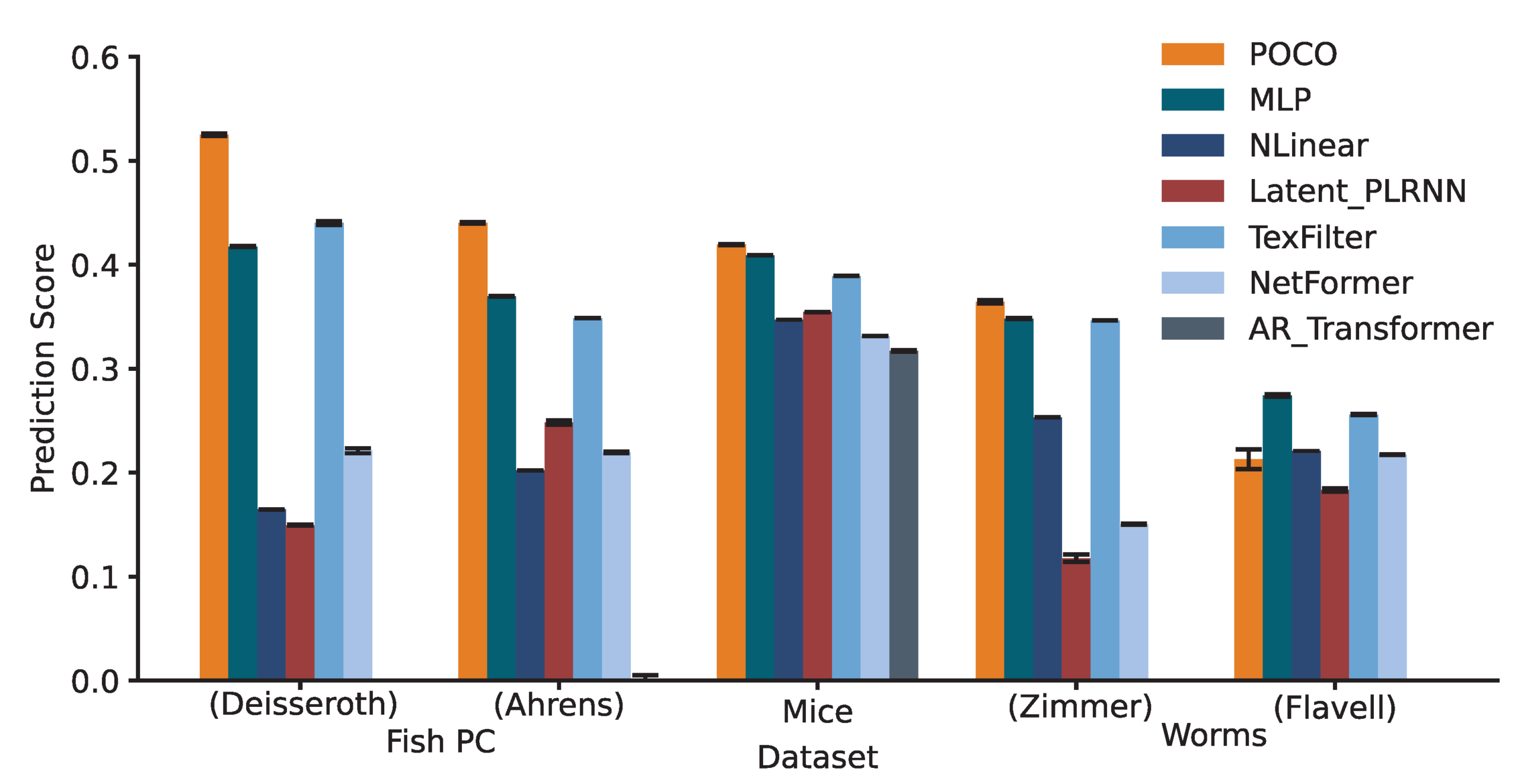

We benchmarked POCO against a wide range of baselines—from simple linear models to complex Transformers—across five datasets spanning three species: Larval Zebrafish, Mice, and C. elegans.

The results established POCO as the state-of-the-art in neural forecasting. Across these diverse datasets, POCO achieved the highest overall prediction scores. Crucially, its performance remained robust over time: while the error for all models naturally increases as we forecast further into the future (up to ~15 seconds), POCO maintained a significant accuracy advantage over baselines at every prediction step. We also observed that POCO successfully leverages longer historical contexts to improve predictions, whereas strictly univariate baselines often fail to utilize extended history effectively. In the ablation study, we find that both the MLP forecaster and the population encoder were necessary for full performance, confirming that conditioning local predictions on the global population state is essential for capturing dynamics.

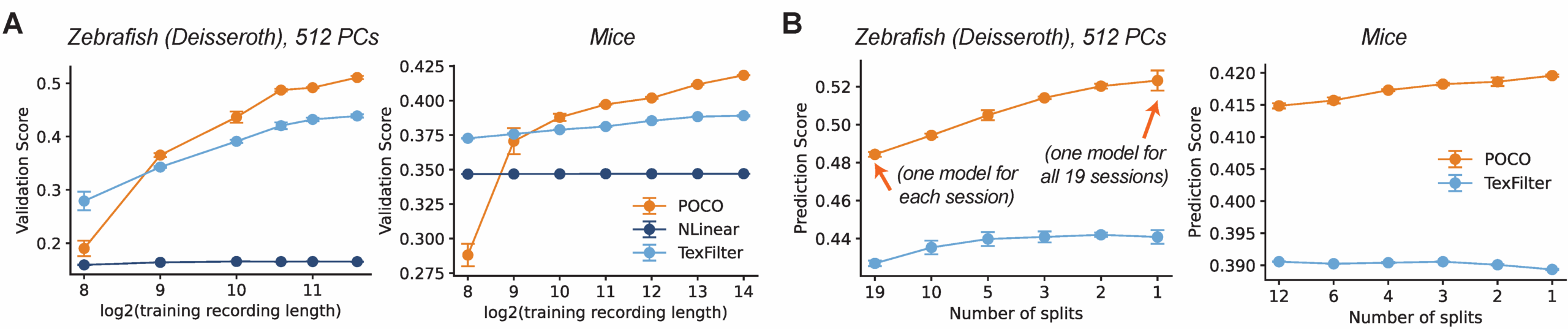

Scaling with Data

We found that POCO effectively leverages scale in two ways. First, as we increased the length of the recording we used for training, POCO’s performance improved steadily, whereas baseline models often plateaued or saw minimal gains. Second, POCO benefits significantly from multi-session training. When we aggregated data from multiple sessions or different animals, POCO outperformed models trained on single sessions alone, suggesting that it learns shared dynamical motifs that generalize across individuals. This ability to aggregate knowledge is a critical step toward general-purpose neural models, distinguishing POCO from classical approaches that are limited to fitting single experimental sessions.

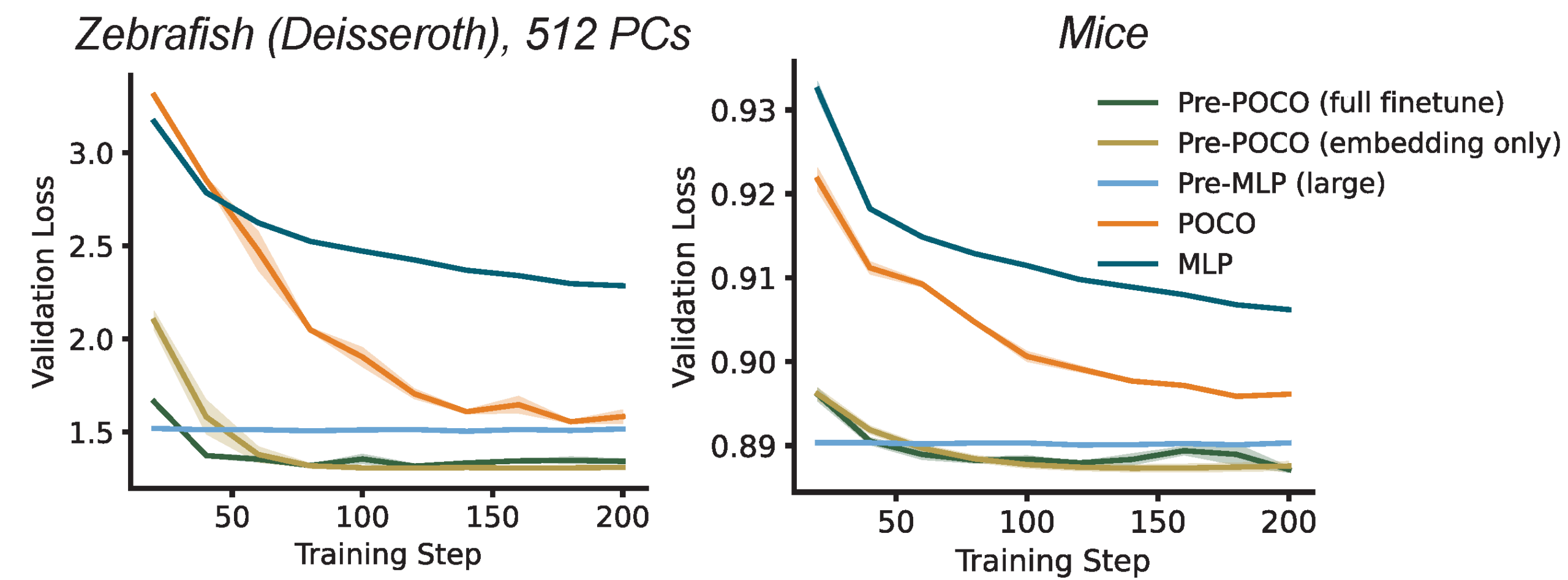

Rapid Adaptation

For a model to be useful in a clinical or experimental loop, it must be quickly adaptable. We treated POCO as a pre-trained foundation model and tested its ability to adapt to new, unseen subjects. By freezing most of the model and fine-tuning only the specific embeddings for the new session, we found that POCO could adapt to a new individual in as few as 200 training steps. Interestingly, we found that updating only the unit embeddings was sufficient to match the performance of fully fine-tuning the entire network. This implies that the core dynamical rules learned by the model are stable, and only the “interface” (the embeddings) needs adjustment. This adaptation takes less than 15 seconds of compute time, and the inference speed is just 3.5 ms per step, making it feasible for real-time calibration in closed-loop experiments.

Interpretable Unit Embedding

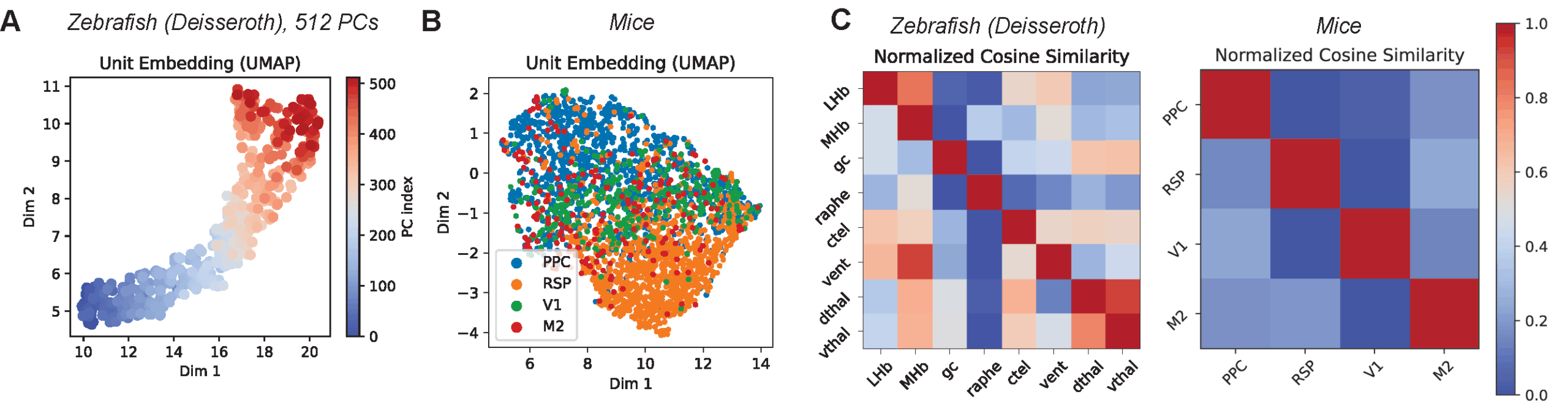

Finally, we analyzed the internal representations—the “unit embeddings”—that POCO learns for each neuron. Importantly, we never provided the model with labels regarding where neurons were located in the brain.

Despite the lack of explicit labels, the model autonomously discovered anatomical structures. When we visualized the learned embeddings, we saw distinct clusters corresponding to anatomical brain regions. For instance, in the mouse cortex, neurons from the Retrosplenial Cortex (RSP) formed a particularly distinct cluster, clearly separated from visual and motor areas. The model learned that neurons in these regions share distinct dynamical properties, effectively “re-discovering” the brain’s functional map purely to solve the forecasting task. This underscores POCO’s dual strength: it is not just an accurate predictor, but also a tool for learning interpretable representations of neural populations.

Summary and Future Directions

In this work, we introduced POCO, a scalable framework for forecasting neural dynamics. We demonstrated that, by conditioning local predictions on global population states, we can achieve state-of-the-art accuracy, scale effectively with data volume, and rapidly adapt to new individuals. We also validated POCO on the external Zapbench benchmark, finding that it performs comparably to computationally expensive volumetric models like UNet at short context lengths, further demonstrating its robustness.

However, challenges remain. We observed that performance gains from multi-species training were limited; simultaneous training on zebrafish and mice did not outperform single-species training, likely due to significant differences in biological dynamics and recording conditions. Future work must address how to better align these distinct domains to build a truly universal foundation model.

Most importantly, to fully realize the potential of closed-loop control, we need to extend this framework beyond passive forecasting. The next frontier is to model the effect of control inputs—predicting not just how the brain will evolve naturally, but how it will respond to external perturbations (e.g. optogenetic stimulation). Integrating these control signals into the foundation model architecture will be key to moving from observation to intervention, paving the way for adaptive neurotechnologies that can interact with the brain in real-time.

Acknowledgements

This work was a collaborative effort involving Hamza Tahir Chaudhry, Misha B. Ahrens, Christopher D. Harvey, Matthew G. Perich, and Karl Deisseroth. The research was supervised by Kanaka Rajan.

This work was supported by the NIH (RF1DA056403), James S. McDonnell Foundation (220020466), Simons Foundation (Pilot Extension-00003332-02), McKnight Endowment Fund, CIFAR Azrieli Global Scholar Program, and NSF (2046583).