New Study Sheds Light on the Brain’s “Extended Language Network”

A new neuroscience study, led by Kempner Graduate Fellow Colton Casto (left), and co-authored by Kempner Research Fellow Greta Tuckute (right), systematically examines parts of the cerebellum that contribute to language processing in the human brain.

Photo credit: Anthony Tuliani

At a glance

- A new neuroscience study published in the journal Neuron systematically examines parts of the cerebellum that contribute to language processing in the human brain.

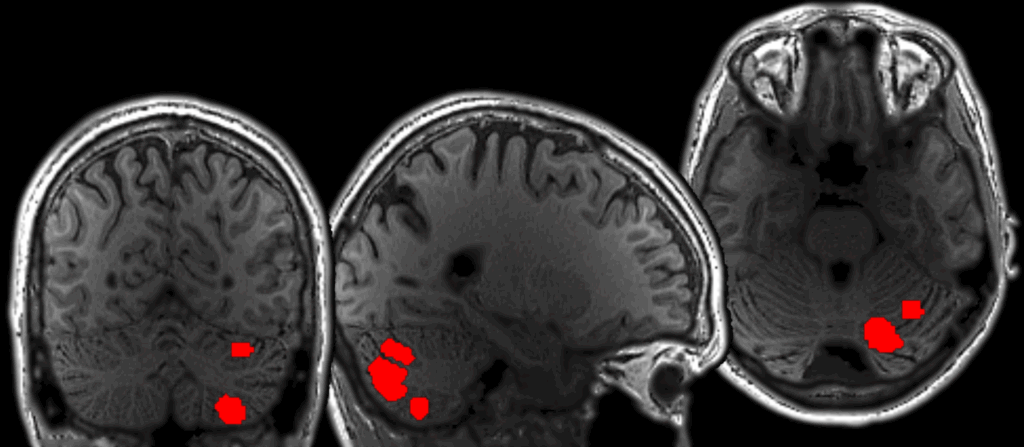

- The study employs precision human neuroimaging, identifying language-related brain regions in individual human subjects without blurring responses through averaging across multiple brains.

- The study finds that activity in one region of the cerebellum closely mirrors the language areas in the cerebral cortex, which are the parts of the brain typically associated with processing language.

For more than a century, scientists studying how the brain processes language have focused their attention on the cerebral cortex, specifically the left frontal and temporal lobes. But a new study by a team of Harvard and MIT researchers draws attention to a neglected collaborator in language processing: the cerebellum, an evolutionarily ancient structure that was historically associated with motor learning.

The study, recently published in the journal Neuron, provides evidence that language processing relies on an extended network of brain regions. Specifically, the researchers found three cerebellar regions showing mixed responses to language and to non-linguistic tasks, and one region that is selectively tuned to language in much the same way as established cortical language areas.

“When you put someone in a scanner and have them listen to a story or read a sentence, you consistently see the cerebellum light up as well,” says Colton Casto, the lead author of the study and a graduate fellow at the Kempner Institute for the Study of Natural and Artificial Intelligence. While the participation of the cerebellum in language is well established in the field, Casto and his collaborators went further, building on rich datasets to probe the nature of its contribution to language processing.

The study’s senior author was Ev Fedorenko, an associate professor at MIT, faculty member in Harvard’s Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and Harvard Medical School’s Speech and Hearing Bioscience and Technology (SHBT) program, and a pioneer in the use of fMRI to study the brain’s language centers.

A clearer picture of cerebellar language processing

Numerous previous studies have reported cerebellar involvement in language, but the question of whether the cerebellum contains regions that are dedicated solely to these processes remains subject to debate. The exact nature of the linguistic processes these regions perform also remains to be determined.

In this study, researchers used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine brain activity in human participants performing 26 tasks, including reading, listening, speaking, solving math problems, completing memory exercises, and processing visual stimuli. This allowed the team to compare how different cerebellar regions responded to linguistic and non-linguistic demands.

“What we wanted to do was a systematic characterization of language-responsive regions in the cerebellum,” says Casto, “and ask a very basic question: what are these regions actually contributing to language processing?”

Casto describes this work as part of a broader effort to chart out the brain’s “extended language network,” which he describes as “the set of brain areas that are recruited when we understand language, beyond the cortical language regions that have received most of the attention in neuroscience.”

Distinctive information processing in the cerebellum

Casto and his team found four regions in the cerebellum that respond to language, but, importantly, the regions did not all respond in the same way. One region responded exclusively to language. The remaining three cerebellar regions showed a different response profile. In addition to language, they were active during motor tasks, demanding non-linguistic tasks, and/or the processing of meaningful visual stimuli.

Casto and his collaborators describe this pattern as “mixed selectivity,” and argue that it might reflect a distinctive type of information processing.

“These are unusual patterns that we don’t really see in the cortex,” says Casto. He and his collaborators suggest that mixed selectivity could be evidence that these cerebellar regions integrate linguistic and non-linguistic information sent there from the cortex: an exciting possibility, given that there are very few proposals for how this kind of integration might take place.

Casto notes that clinical evidence also indicates that the cerebellum’s contributions differ from those of the cortex in important ways. Damage to cortical language regions can result in “global aphasia,” which is a profound loss of language ability. Cerebellar damage, by contrast, tends to produce subtler language impairments, which is one reason its role in language processing has historically been overlooked.

Why earlier studies missed the pattern

A key reason these cerebellar patterns have been difficult to detect in past studies lies in how most fMRI studies are conducted. Typically, researchers average brain activity across many participants to identify regions that respond reliably to a given task. While powerful, this approach can obscure fine-grained organization, especially in a structure like the cerebellum, where regions performing distinct functions are densely packed and vary substantially from one individual to the next.

“If you average across brains, then you get a really blurry picture,” says Casto.

Instead, Casto’s team localized language-responsive regions within each participant’s cerebellum before examining how those individualized regions responded across tasks.

“A key part of this work is localizing language-responsive regions within individual brains rather than relying on group averages,” says Casto. “Historically, few cerebellar studies have used this approach.”

This individual-level analysis had the power to disentangle overlapping signals that would otherwise be smeared together, producing a much sharper understanding of cerebellar involvement in language.

The scale of the study also contributed to the power of the findings. “More than 800 unique human subjects were scanned, across a very diverse set of experiments,” says Greta Tuckute, a co-author of the study and a research fellow at the Kempner Institute.

Implications for language and beyond

The findings raise intriguing questions for further research, including how cerebellar language regions interact with cortical networks and how their contributions to language processing might change as a child grows up.

The results may also indirectly inform future research in artificial intelligence. “I’m very interested in developing more biologically-inspired architectures for language models,” says Casto. “My hope is that in five to ten years — as our understanding of the neural architecture of language evolves — we will be able to design more efficient and reliable artificial systems.”

While the implications for future AI systems remain to be investigated, the study’s significance for neuroscience is clear: language processing is supported by a network that extends well beyond the cerebral cortex, and the cerebellum is a key player in that network.