A Neuroscientist in Search of an Answer

Arturo Deza’s paintings, on display at the Kempner Institute, consider the complexity of perception in humans and machines

Arturo Deza, a neuroscientist and artist, stands beside three of his paintings that are now on display at the Kempner Institute.

Photo credit: Anna Olivella

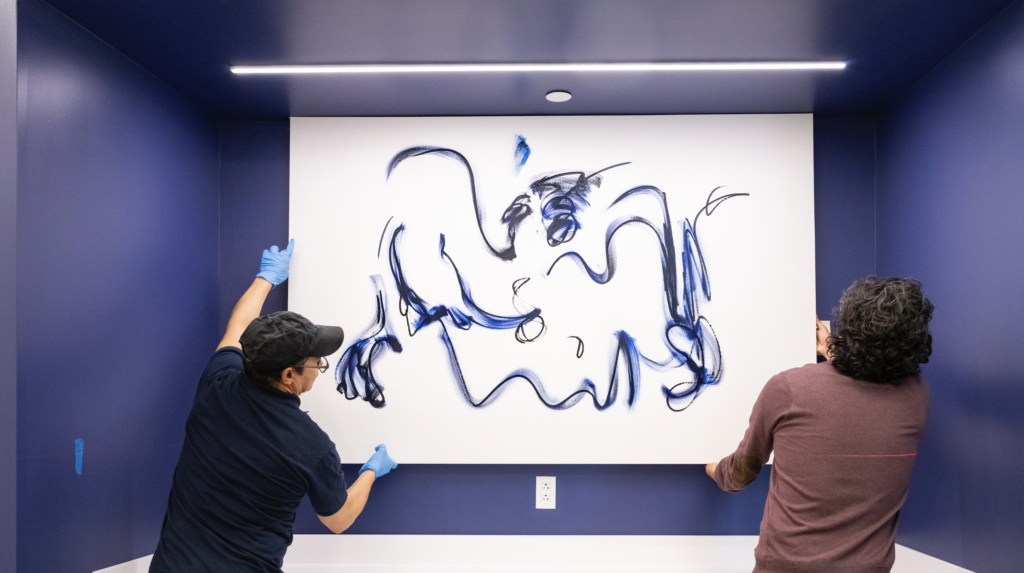

With bold brush strokes and vivid blues set against bright whites, Arturo Deza’s paintings, now on display at the Kempner Institute, are a testament to the idea that meaning, both in science and in art, often emerges in unforeseen ways.

As a professional neuroscientist and artist, Deza combines his expertise in the science of vision with an improvisatory painting style. His artwork is inspired by concepts in neuroscience and machine learning, where he studies the convergences and the divergences in how both humans and machines see.

Deza completed his postdoctoral studies at Harvard, and says the Kempner Institute feels like a natural place to display his work. “I was a postdoc at Harvard before the Kempner was founded, and I worked with Talia Konkle, who is now an associate faculty member at the Institute,” he says. “Some of the pieces that I’m showing at the Kempner were partially inspired by the work I did at Harvard.”

Deza recently visited the Kempner Institute from Peru, where he is now assistant professor in computer science at Universidad de Ingeniería y Tecnología. The Kempner Institute’s science writer Yohan John sat down with Deza to discuss his paintings on loan to the institute.

Tell us a little bit about how your science and your art come together.

Most of my research focuses on visual perception – how humans see. That’s what I did for my Ph.D. and my two postdocs, one at Harvard, and one at MIT. The Kempner Institute combines the study of biological and artificial intelligence. I do that for vision; I study the convergences and the divergences between how humans see and how machines see.

There are interesting types of stimuli to probe these similarities and differences between natural and artificial visual systems. We sometimes use “out-of-distribution” stimuli. In the context of machine learning, these are stimuli that were never part of the training data. We can view certain kinds of art as out-of-distribution stimuli: these are images that are in some sense “unnatural,” so humans are unlikely to have seen them before.

So with a computer vision system, if you show it a phone, the system will recognize that it’s a phone. You show it a ball and it sees a ball. But things start to get interesting when you show an artificial system images that are very complex, like art, or random images, and you force the system to make a decision about what it sees. So some of the work I was doing in my postdoc [at Harvard] influenced the style I have now. I play with preserving the overall shape of an object, but when you look closer, the details are not the same.

Is this related to the Rorschach test? Do you ‘psychoanalyze’ computer vision models?

Exactly. Rorschach was an artist himself. He made his inkblot patterns and one day realized that different people see different things. And we do something like that with computer vision models; it’s like a guessing game. We show the models images that they’ve never seen in training and ask them to decide what is being shown.

An interesting aspect of my work is that I don’t have a predefined sketch. So it’s more just me thinking about a specific concept. Sometimes, I’ll improvise about an idea, an object, a place, or a situation. And in the heat of the moment, I put my mind into painting. An interesting challenge is that I have to decide when to stop. And that’s really complicated because I could always do another brush stroke, right? It’s not obvious how to conclude a painting. Even from a scientific point of view, there is a sense of entropy equilibrium, or of creating a complete stimulus that is not fully random, but is also not too obvious. If it’s too obvious and it kind of spoils the whole guessing game of what the painting represents.

This reminds me of the line “A poem is never finished, only abandoned.”

Exactly.

And that’s also a good point for us to segue into the painting that’s in front of us. What’s the story behind it?

This one is called “The Majestic.” I did it around 2022. I was in a transitioning period of my life. I was finishing my postdoc at MIT and I had already developed this new style. I wanted to play with the idea of bi-stable or multi-stable stimuli using just one color. This one is just one particular shade of blue on a plain white canvas, and it involves the continuous movement of brushstrokes. It was probably done in around fifteen minutes. It was really fast. You have to not think when you do it. Because if you think, then things don’t work out. So that’s how this one was done. And when I was painting it, I was thinking about some sort of ominous creature. It looks like a bird with two hands. It’s kind of like a guardian. Maybe not an angel, but it’s this majestic floating creature.

But I also don’t like to say that. Someone might say, oh, here I see an elephant. Each person might see something different, like waves, or a ball. And yet the sentiment most people get is very similar. Sometimes people still diverge. Someone will say this painting makes me happy. Someone it makes them feel sad. Someone will say it’s aggressive. Someone will say it’s passive.

Tell us a little bit about your improvisation methods.

I always like to paint at night and it’s not something I do every day – maybe once every week or two. I like to be in some sort of important emotional state to do it. I think some people paint more as a discipline, every day. I can’t do that. I like to get into a very relaxed state and then give myself a limit. I might decide to paint for at least 15 minutes, but not more than an hour.

This is a little bit like a generative AI system. I have a prompt in my mind – I want to paint this feeling with these colors in this tone and this time with these conditions – and based on that I’ll just see what happens.

What’s the story behind the painting “A Dog in Search of Love”?

Oh, that’s one of my favorite paintings here! That was from a very emotional phase of my life. I was living with a new partner. Some people say a romantic relationship is easy but that’s not always the case. You have to work on it. So I played with the idea of a dog looking. It’s almost a sensual representation of a dog, but the dog is also somewhat spiritual. And there’s this red patch that looks like a teardrop. Like it’s crying blood. These are things I interpreted later – I didn’t plan it ahead. I just wanted to paint something about how I felt. And then something else emerges.

Now when I look at it as I walk to my office, I’m going to be thinking of a scientist in search of an answer.

Right. In science, searching for an answer is going to be difficult. There are going to be complexities.

Do you have any words of advice for scientists who are also artists?

The most important thing is to just do it. The important thing is that you enjoy it and eventually, as you iterate over time, you’ll find your own voice or style. I never went to art school, but maybe that is not a bad thing because I have my own set of rules when I paint. But of course, there’s always this fear. What if the painting doesn’t turn out right? You just don’t know what’s going to happen. I think that’s also the fun of it. It could turn out great. It could turn out terrible. It almost never turns out terrible. I think you just have to just let go and be free.

Note: This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

About the Kempner Institute

The Kempner Institute seeks to understand the basis of intelligence in natural and artificial systems by recruiting and training the next generation of researchers to study intelligence from biological, cognitive, engineering, and computational perspectives. Its guiding principle is that natural and artificial forms of intelligence share important characteristics. Future innovations in artificial intelligence (AI) will take inspiration from the principles that our brains use for fast, flexible natural reasoning. In parallel, theories developed for AI will enhance our understanding of how our brains compute and reason. Join the Kempner mailing list to learn more, and to receive updates and news.

PRESS CONTACT:

Deborah Apsel Lang | (617) 495-7993 | kempnercommunications@harvard.edu