Measuring and Controlling Solution Degeneracy Across Task-Trained Recurrent Neural Networks

February 03, 2026Despite reaching equal performance success when trained on the same task, artificial neural networks can develop dramatically different internal solutions, much like different students solving the same math problem using completely different approaches. Our study introduces a unified framework to quantify this variability across Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) solutions, which we term solution degeneracy, and analyze what factors shape it across thousands of recurrent networks trained on memory and decision-making tasks.

What is solution degeneracy?

Imagine a classroom of students given a complex math problem. They all arrive at the correct answer, but if you ask them to show their work, you realize they all used completely different methods. Some used algebra, others geometry, and some just memorized a pattern. Artificial neural networks are surprisingly similar. When we train multiple RNNs on the same task, they often reach the same high performance (the “correct answer”) on the training set but develop drastically different internal mechanisms to get there. This variability is called solution degeneracy.

Understanding this phenomenon is important because RNNs are widely used in neuroscience and machine learning to model dynamical processes. For computational neuroscientists, these networks are essential for generating hypotheses about the neural mechanisms underlying task performance. Traditionally, however, the field has focused on reverse-engineering a single trained model, implicitly assuming that networks trained on the same task will converge to similar solutions. Yet, that assumption is not always guaranteed.

This raises a fundamental question: What factors govern solution degeneracy across independently trained RNNs? And, if the solution space is highly degenerate, to what extent can we trust conclusions drawn from a single model instance?

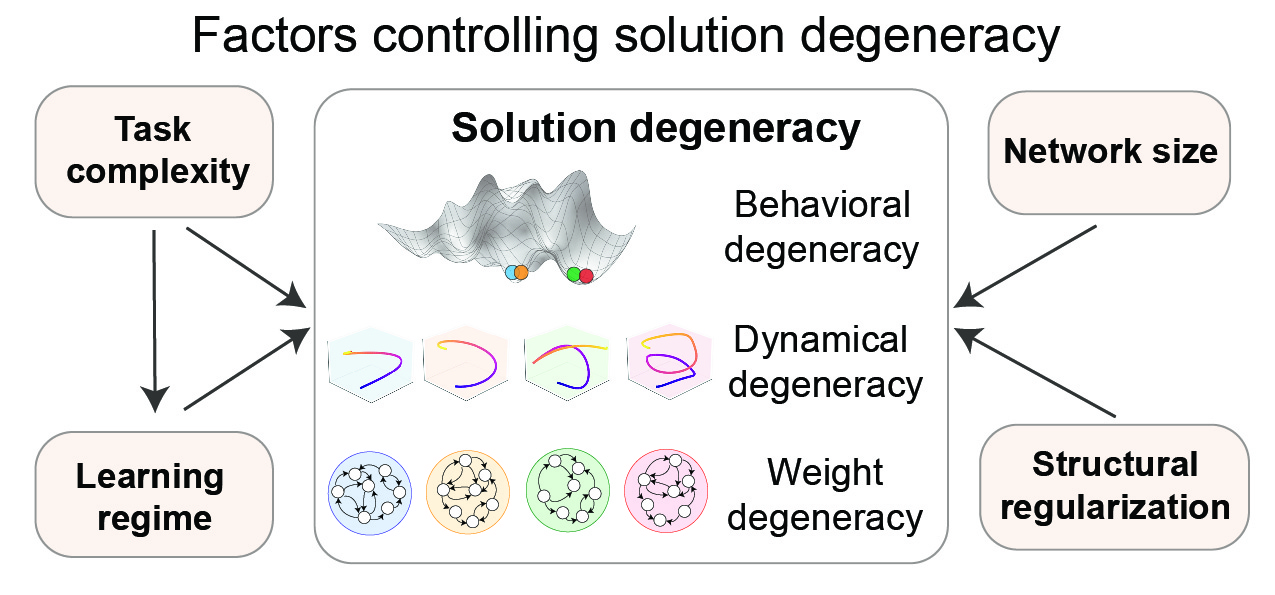

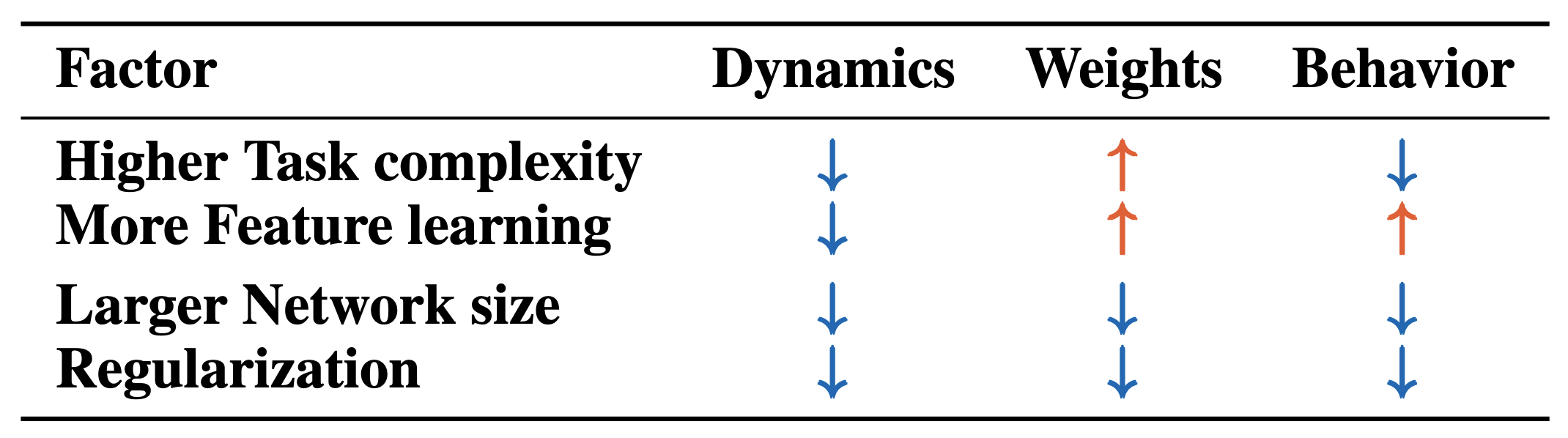

To address this, we introduced a unified framework for quantifying solution degeneracy at three distinct levels: behavior, neural dynamics, and weight space. Leveraging this framework, we isolated four key factors that control solution degeneracy: task complexity, learning regime, network width, and structural regularization. We find that higher task complexity and stronger feature learning reduce degeneracy in neural dynamics while these factors increase weight degeneracy, with mixed effects on behavior. In contrast, larger networks and structural regularization reduce degeneracy at all three levels. Below, we dive into our unified framework and how we used it to map the landscape of solution degeneracy.

Multi-level framework for quantifying solution degeneracy

To understand how different two networks are, we developed a framework to quantify degeneracy across three distinct levels: behavior (network output), neural dynamics (hidden state activities), and weights level.

Behavioral degeneracy: Even when networks perform equally well on the training task, their behavior may diverge when tested on a new task. We measure this by testing their temporal generalization capacity – challenging the networks to handle sequences twice as long as those they were trained on. Degeneracy here is defined as the variability in these out-of-distribution (OOD) responses.

Dynamical degeneracy: Because RNNs perform computations through time-varying trajectories, we compare the topological structure of their neural trajectories (time series of their hidden state activities) using Dynamical Similarity Analysis (DSA). Unlike traditional geometry-based methods, DSA is robust to noise and has proven more effective at concretely identifying behaviorally relevant differences in neural activity.

Weight degeneracy: Finally, we look at the connectivity of the networks. We quantify weight-level degeneracy by measuring the distance between the recurrent weight matrices of two networks. Since the specific numbering of neurons doesn’t change a network’s function, we use a permutation-invariant version of the Frobenius norm to ensure we are comparing the actual connectivity patterns rather than just their arbitrary labels.

Task suite for diagnosing solution degeneracy

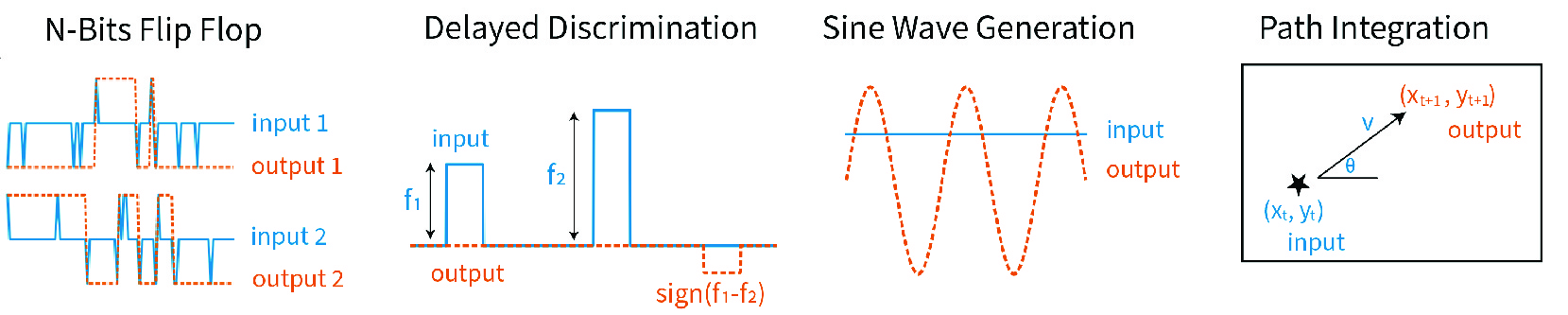

We put this framework to the test using 3,400 vanilla RNNs trained on four tasks that mirror the computational problems faced by biological brains. Each task was chosen to elicit specific neural dynamics commonly studied in neuroscience. The selected tasks have also been used in prior benchmark suites for neuroscience-relevant RNN training, underscoring their broad relevance for studying diverse neural computations.

- N-Bit Flip-Flop: A test of pattern recognition and memory retrieval, analogous to Hopfield-type attractor networks that store discrete binary patterns and retrieve them from partial cues.

- Delayed Discrimination : A classic working memory paradigm where the network must hold a value in mind across a delay to make a later comparison.

- Sine Wave Generation: A pattern generation task which requires the network to produce self-sustaining, rhythmic cycles, analogous to the role of Central Pattern Generators (CPG), a self-organizing biological neural circuit.

- Path Integration: A test of ability to track position over time by integrating self-motion cures, without relying on external landmarks. This task is inspired by hippocampal and entorhinal circuits that build a cognitive map of an environment.

On each task, we trained 50 discrete-time vanilla RNNs governed by the update rule: $h_t = \tanh (W_h h_{t−1} + W_ x x_t + b)$. In all experiments, we train networks until they reach a near-asymptotic, task-specific mean-squared error (MSE) threshold on the training set, after which we allow a patience period of 3 epochs and stop training to measure degeneracy.

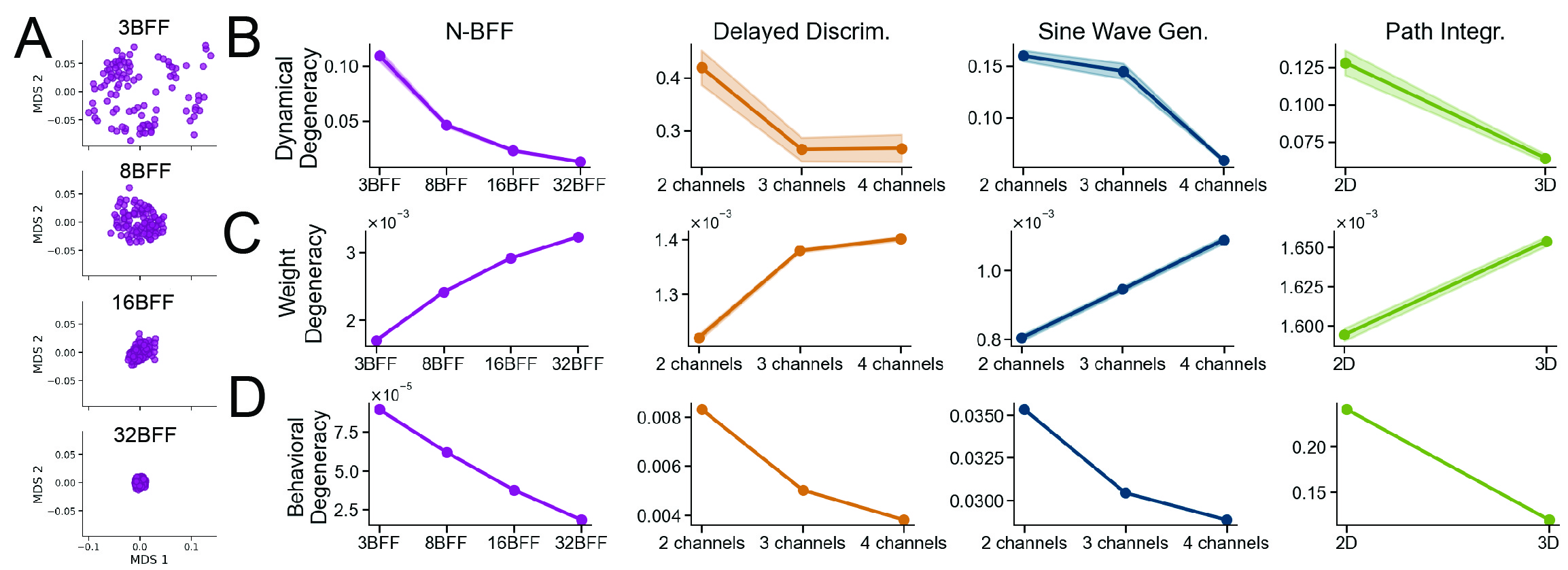

Harder tasks induce more similar neural dynamics and OOD behavior, but more divergent weights

Previous research hypothesized that as tasks grow more complex, the “room” for different solutions should shrink. This is known as the Contravariance Principle: because harder tasks impose stricter constraints, fewer models should be able to satisfy them simultaneously, leading to more consistent solutions.

To put this principle to the empirical test, we scaled task complexity in several ways:

- Increasing task dimensionality: We varied the number of independent input–output channels, forcing networks to solve multiple mappings at once.

- Adding memory demand: We increased the delay period length in Delayed Discrimination, raising the “memory demand”.

- Adding objectives: We introduced auxiliary losses, requiring the network to track multiple pieces of information simultaneously.

Across every task, we found that higher demands act as a funnel for the network solution. These complex tasks constrained the space of viable solutions, leading to much greater consistency in neural dynamics and OOD behavior. Essentially, when the problem is hard, there are fewer ways to solve it successfully.

However, the weight level told a paradoxically different story. Even as the dynamics became more similar, the weight matrices actually grew more divergent as complexity increased.

Why do weights diverge while dynamics converge? We hypothesize that this paradox reflects an increased dispersion of local minima in the weight space for harder tasks. A helpful way to visualize this is through the concept of intrinsic dimension—essentially, the lowest-dimensional weight subspace required to find a solution. As a task becomes more complex, this intrinsic dimension expands. Consequently, each solution comes to occupy a thinner slice of a higher-dimensional space, causing the resulting minima to lie further apart.

In the next section, we explore a second mechanism for this divergence: how task complexity interacts with a network’s learning regime to amplify this weight-space variety.

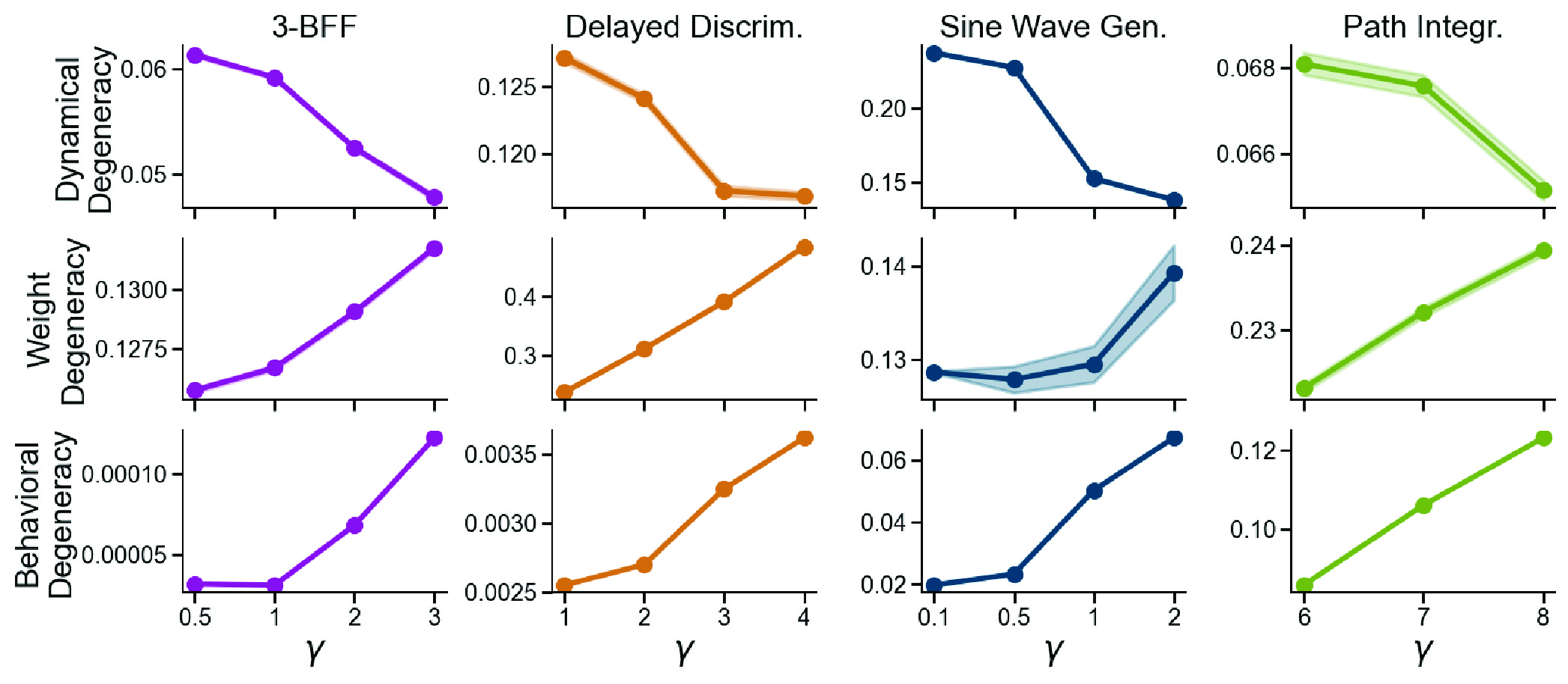

Feature learning induces more consistent dynamics and more divergent weights and OOD behavior

In deep learning theory, neural networks can solve a task in two very different ways. In the “lazy learning” mode, they rely heavily on the random features they happened to start with, like a student who plugs numbers into a memorized formula without really understanding the problem. On the other hand, in the “feature learning” mode, the network actively reshapes its internal representations to capture the structure of the task, more like a student who learns the underlying concept and builds a more structured way of thinking about the problem.

We found that complex tasks force RNNs out of their lazy comfort zone into stronger feature learning. As task difficulty grows, random initialization is no longer sufficient; the network must adapt. Because feature learning networks have to travel further from their initialization to build these new features, their final weight configurations end up far more dispersed than those of lazy networks, resulting in greater weight degeneracy.

But does feature learning cause these changes in degeneracy, or is it just a byproduct of increased task complexity? To test this, we used the Maximum Update Parameterization ($\mu P$), where a single hyperparameter ($\gamma$) controls the strength of feature learning. Here, the RNN output is downscaled by $\gamma$: $f(t) = \frac{1}{γN} W_{readout} \phi(h(t))$ and larger $\gamma$ induces more feature learning.

We observe that when $\gamma$ is high (stronger feature learning), these networks actively reshape themselves to discover similar task-specific features, converging on consistent neural dynamics and OOD behavior. Conversely, “lazy” networks (low $\gamma$) remain tethered to their random initialization, leading to idiosyncratic and divergent solutions across different seeds.

Interestingly, while the neural dynamics converge, the out-of-distribution behavior diverges. We hypothesize that strong feature learning drives networks to overfit the training task, rendering them hypersensitive to feature shifts in out-of-distribution conditions. This decoupling underscores that aligning internal dynamics does not automatically guarantee more consistent generalization behavior.

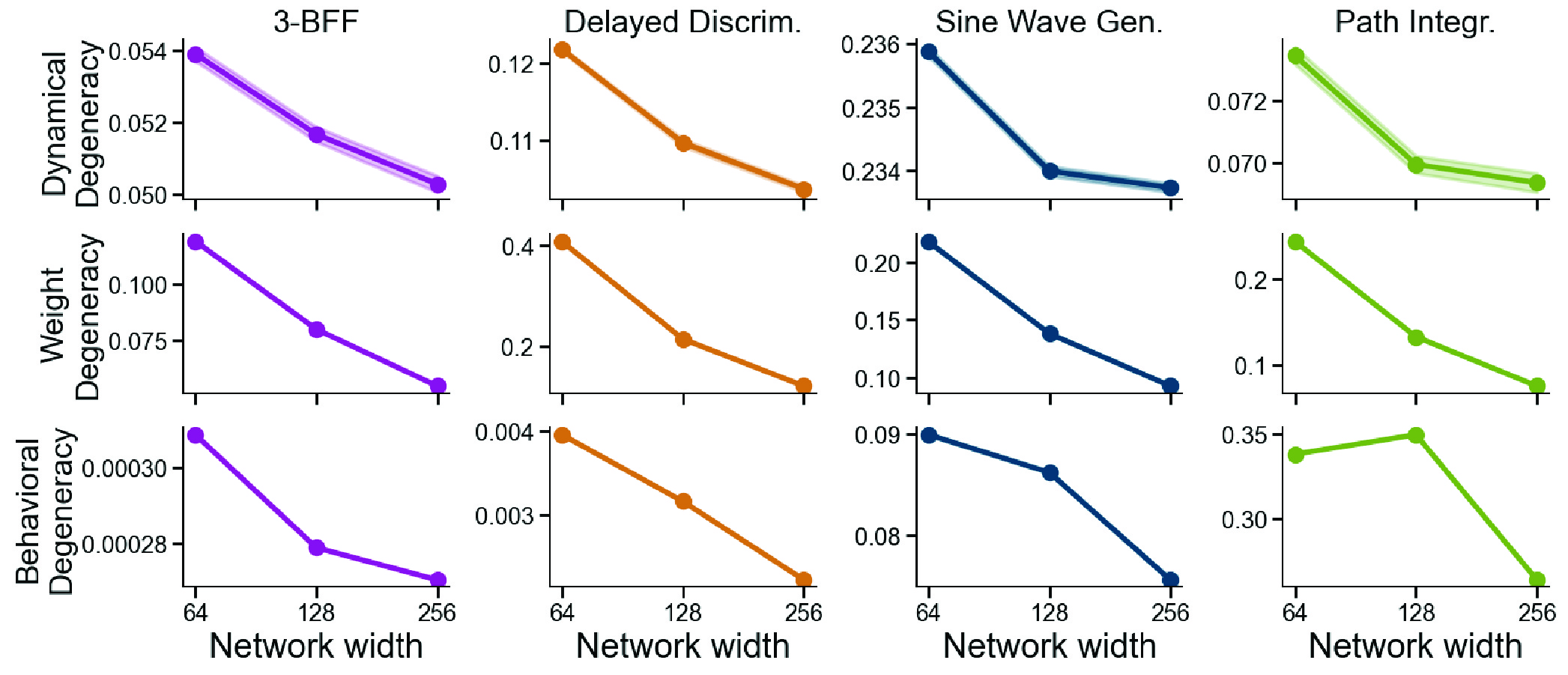

Larger networks yield more consistent solutions across levels

Prior work in machine learning and optimization shows that over-parameterization improves convergence by helping gradient methods escape saddle points. We therefore hypothesized that larger RNNs would converge to more consistent solutions across seeds.

To test this, we had to be careful because simply scaling a network’s size usually pushes it into a “lazy” learning regime. To isolate the size effect, we again used the $\mu$ parameterization to hold the feature learning strength constant while scaling the network width.

Across all tasks, larger networks consistently exhibit lower degeneracy at the weight, dynamical, and behavioral levels, producing more consistent solutions across random seeds. That is a clear convergence-with-scale effect demonstrated on RNNs, across neural dynamics, behavior, and weights.

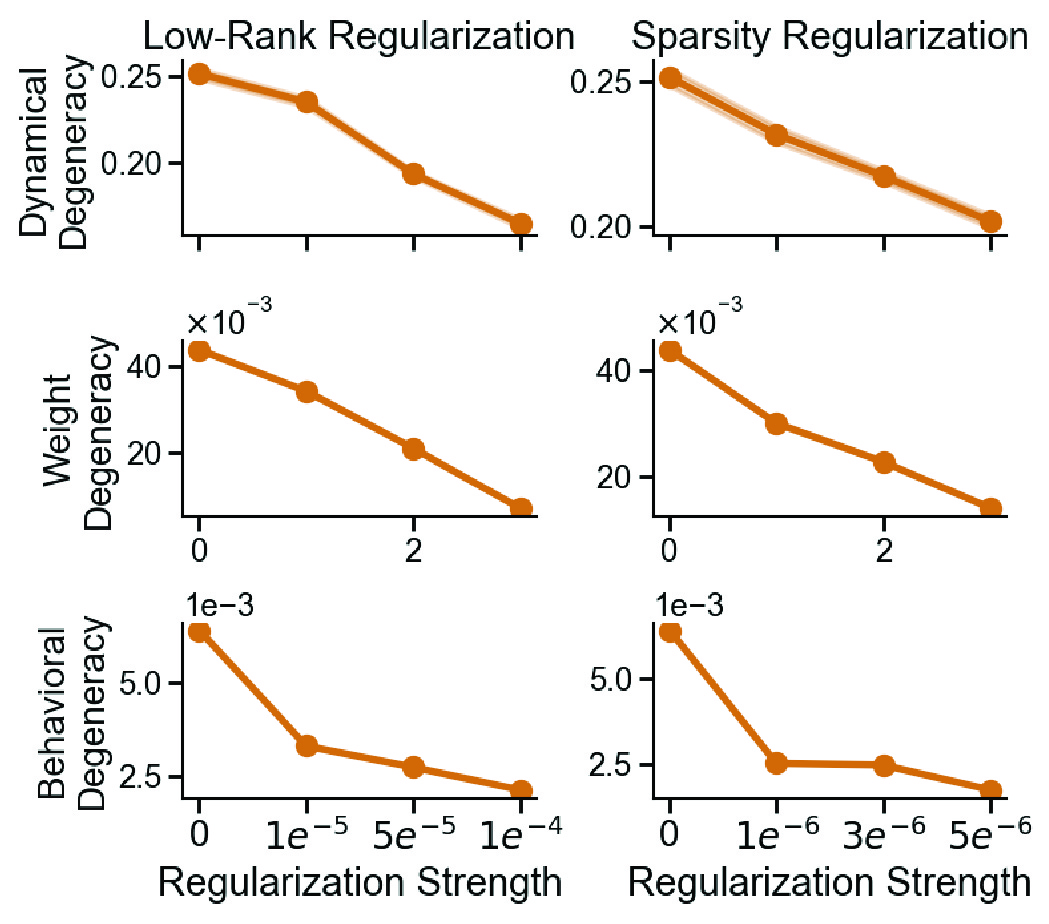

Regularization reduces degeneracy across levels

Finally, we looked at structural regularization. In both computational neuroscience and machine learning, we often impose constraints to make models more efficient, interpretable, or biologically plausible — specifically sparsity ($L_1$, driving parameters to zero) and low-rank (forcing activity into a few dominant modes) regularization.

We reason that for both regularizations, task-irrelevant features are pruned, nudging independently initialized networks toward more consistent solutions on the same task. This intuition held true. We found that both low-rank and sparsity constraints consistently reduced degeneracy across all three levels: behavior, dynamics, and weights.

Implications: A field guide for neural variation

Our findings provide a practical roadmap (summarized in Table 1 of the paper) for researchers to “tune” the individuality of their models to suit their goals.

- Finding Commonality: If your goal is to uncover shared mechanisms underlying during a task, you should aim to suppress degeneracy. Use larger networks, regularization, or harder tasks to force models to converge on a common solution.

- Modeling Individuality: Conversely, if you want to study individual differences, you can purposely increase degeneracy. By using smaller networks or “lazy” learning regimes, you can generate a diverse population of solutions that mimics the variability seen across biological subjects.

While our work focuses on artificial networks, these mechanisms offer a new lens for experimental neuroscience. For example, introducing an auxiliary sub-task during behavioral shaping, which mirrors our auxiliary-loss manipulation, could constrain the solution space animals explore, thereby reducing behavioral degeneracy [94]. Finally, our contrasting findings motivate theoretical analysis, e.g., using linear RNNs to understand why some factors induce contravariant versus covariant relationships across behavioral, dynamical, and weight-level degeneracy.

Conclusions

Our work addresses a classic puzzle in task-driven modeling: What factors shape the variability across independently trained networks? To address this, we introduced a unified framework for quantifying solution degeneracy in task-trained RNNs at three complementary levels: behavior, neural dynamics, and weights.

By systematically sweeping task complexity, feature learning strength, network size, and regularization strength, we uncovered two distinct regimes of variability. First, increasing task complexity or enhancing feature learning produced a contravariant effect: dynamical degeneracy decreased while weight degeneracy increased. Second, increasing network size or applying structural regularization produced a covariant effect, reducing degeneracy at both the weight and dynamical levels. Crucially, we also found that more similar in-distribution neural dynamics do not necessarily translate to consistent out-of-distribution (OOD) behavior.

By identifying the factors that shape the solution landscape, we move beyond treating variability as random noise. Instead, we can treat it as a controllable feature, building models that are as consistent (or as diverse) as the biological systems we seek to understand.