A New Kind of AI Model Gives Robots a Visual Imagination

Kempner researcher Yilun Du and his team introduce a breakthrough system that could redefine how robots learn to act in the physical world

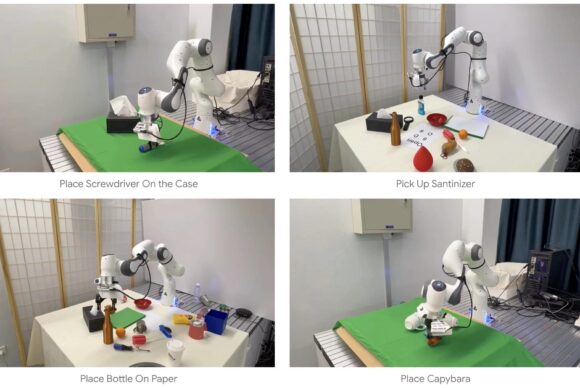

Video stills show a robot gripper generalizing its knowledge to perform specific actions in response to prompts, such as picking up a screwdriver and placing it on a case, or picking up a bottle of hand sanitizer.

In a major step toward more adaptable and intuitive machines, Kempner Institute Investigator Yilun Du and his collaborators have unveiled a new kind of artificial intelligence system that lets robots “envision” their actions before carrying them out. The system, which uses video to help robots imagine what might happen next, could transform how robots navigate and interact with the physical world.

From Language to Vision: A Shift in Robotic Intelligence

This breakthrough, described in a new preprint and blog post, marks a shift in how researchers think about robot learning. In recent years, researchers have developed vision-language-action (VLA) systems — a type of robot foundation model that combines sight, understanding, and movement to give robots general-purpose skills, reducing the need for retraining the robot every time it encounters a new task or environment.

Yet even the most advanced systems, most of which rely heavily on large language models (LLMs) to translate words into movement, have struggled to effectively teach robots to generalize knowledge in new situations. So, instead, Du’s team trained its system using video.

“Language contains little direct information about how the physical world behaves,” said Du. “Our idea is to train a model on a large amount of internet video data, which contains rich physical and semantic information about tasks.”

Teaching Robots to Imagine the Future

Using the Kempner AI Cluster, one of the most powerful academic supercomputing resources available, Du and his team encoded information from vast troves of internet videos into a “world model,” which is the robot’s internal representation of the physical world.

Crucially, this lets the robot generate short, imagined video clips of future scenarios.

“The video generation capabilities learned from internet data help transfer knowledge to the robot foundation model,” says Du. “The idea is to synthesize videos showing how a robot should act in a new task.”

In other words, the robot can simulate possible futures, visualizing what might happen before it moves. The researchers demonstrated that this “visual imagination” allows robots to perform a wide range of tasks in unfamiliar environments.

“So we have a model that can broadly anticipate possible future actions in an environment,” says Du.

The Challenge of Physical Intelligence

Du’s findings underscore a key insight about intelligence itself. While humans often associate intelligence with abstract problem-solving — the kind used in math or chess — true physical intelligence involves navigating a complex, ever-changing world.

“Physical intelligence is challenging because of the enormous diversity of environments,” Du says. “As you go through life — from your home to the outdoors, to a museum, underwater, or in the sky — you can still perceive, adapt, and navigate effectively, no matter how different the surroundings are.”

Another challenge is that physical intelligence often unfolds over time. “You’re not just making one move: you must coordinate many actions in the right order to complete a task successfully,” Du says. “With something like chess, you can see the entire board and decide on a single move. In physical intelligence, there’s much stronger temporal dependency.”

Du and his collaborators are paving the way towards robots that use video to anticipate not just the next move, but a chain of consequences. “In video generation, the model predicts how the world will evolve visually, which aligns more closely with physics than language does,” Du says.

Toward Robots That Understand Like Living Creatures

By developing a robot foundation model grounded in sensory patterns rather than language, Du’s team is nudging robotics toward a more biological form of understanding. “We didn’t evolve to play chess,” Du points out. “But we did have hundreds of millions of years of evolution to develop intelligent motor control.” That evolutionary insight has profound implications for AI. “It seems that the right way to develop intelligent robots is not by training models primarily on language information,” Du says. “Language didn’t teach us how to interact in the physical world.”

Looking ahead, the researchers aim to link this visual imagination with long-term planning and memory. “For example, if you give a robot long-term goals, like navigating a house, how does it remember its past experiences?” Du asks. He believes the new robot foundation model could help answer that question.

The team also plans to test the model in more dynamic, real-world scenarios. “Right now, many of our tasks are in relatively static environments, where the robot can pick up objects and interact without much change,” Du says. “But in more dynamic settings, a robot needs to account for things like object weight or changing conditions. Exploring how to handle those kinds of physical dynamics is another exciting challenge.”